How Payments Work: Clearing and Settlement

How does money actually move from our bank account to the merchant bank account?

In the previous post, we saw how the Authorization process works. Now, let’s examine the steps that follow a payment authorization: the Clearing and Settlement phases.

The swipe of the card, referred to as the Authorization, typically puts a hold on funds in the cardholder’s account. So, for example, if you look at any of your credit card or debit card online statements, you will see a section at the top of the screen showing “Pending Transactions.” This is because the transaction hasn’t officially cleared. In most cases, a transaction will clear the following day, but there could be other instances where it takes longer to clear.

How does money actually move from our bank account to the merchant bank account?

Clearing happens toward the end of the day for most Merchants and will factor in tips, transaction reversals, and returns. This is basically the Merchant confirming these transactions are valid and that these funds are ready to be moved or “settled.” Settlement is the actual movement of money from the cardholder’s bank account, the Issuing Bank, to the Merchant’s bank account, the Acquiring Bank. This movement of money typically happens via Fedwire ( an electronic funds transfer system operated by the U.S. Federal Reserve Banks that enables financial institutions to make large, same-day, and irrevocable payments to each other in real-time) as instructed by the payment networks.

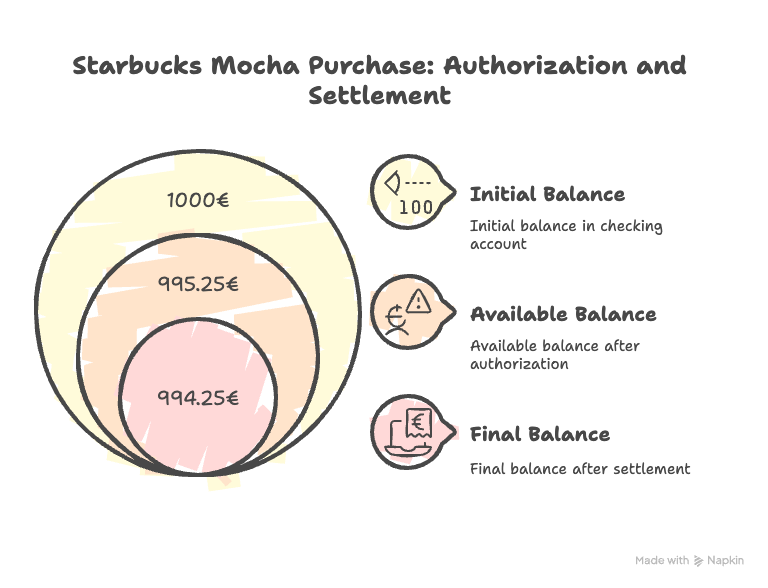

To make the concept of Clearing and Settlement stick, let’s imagine we are purchasing a mocha coffee at Starbucks’. The coffee was 4.75€, and we added a tip of 1€. The Authorization transaction, or the first part of the dual-message transaction, was for 4.75€, and that was approved before we got our mocha. The Issuer Processor checked to make sure that we had at least 4.75€ in our bank account. Our available balance went down before we ordered the mocha; we had exactly 1,000€ in our bank checking account. At the time of Authorization, there was a funds hold placed on 4.75€ out of 1,000€, but at this time, the money hadn’t moved. So, our actual bank balance remained at 1,000€ until the transaction settled. However, our available balance will show up as 995.25€. This means that if we were to go out and try to purchase something for more than 995.25€, the transaction would get declined because it exceeded our available balance.

Our actual balance will go down at Settlement. Now, we will see a transaction of 5.75€( 4.75€+ the 1.00€ tip). Our available balance will be 994.25€ ( 1,000€ beginning balance – 4.75€ for the coffee– 1€ tip). At this point, Mastercard, via Fedwire, has moved the money out of our bank account into the bank account of Starbucks’ Merchant Acquirer. Starbucks’ Merchant Acquirer then sends the money to Starbucks’ bank account via Automated Clearing House (ACH).

During Settlement, the Card Network, Mastercard, does not send to Starbucks the full 5.75€ for our coffee and tip. The Card Network will:

• Keep a percentage of the 5.75€ for itself as the Network Assessment Fee.

• Take a percentage of the 5.75€ and pass it on to the card Issuer as the Interchange Fee.

Transacting via debit or credit card doesn’t cost us anything. However, the Merchant is charged by the card network. So, in this case, Starbucks pays a few fees for this transaction that are netted out of the total transaction value of our mocha. This percentage varies greatly based on:

• Location

• Merchant Type

• Type of card you are using (credit versus debit, and even within these two types, is it a business card or a consumer card, or by card network tiers like “World” and “Platinum”)

• Transaction mode (was it a signature transaction versus a Personal Identification Number (PIN) debit transaction, and how the transaction was done [i.e., was the chip used? Was it done online?])

That’s it.

Understanding the journey from Authorization to Clearing and Settlement reveals the complex choreography that happens behind every card swipe. What seems instantaneous to us—buying a coffee—actually unfolds over hours or even days, involving multiple parties, networks, and systems working in concert.

But here’s something even more fascinating to consider: the numbers you see in your bank account? They’re just that—numbers on a screen. They represent a promise from your bank, not a vault filled with your actual cash. When you see a balance of €1,000, or even €300,000, that money isn’t sitting in a drawer with your name on it. Banks operate on a fractional reserve system, meaning they keep only a small portion of deposits on hand and lend or invest the rest. This is why, if you tried to withdraw €300,000 in cash all at once, your bank would likely need advance notice—the physical money simply isn’t there waiting for you.

In essence, modern banking is built on trust and accounting ledgers. The “available balance” versus “actual balance” distinction we explored with our Starbucks example is just the tip of the iceberg. Every transaction, every balance, every payment is part of an intricate web of settlements that keeps our financial system running smoothly—as long as we all believe in the numbers on the screen.

---

Want to learn more?

This post is part of my upcoming course, where you’ll learn the payment process flow and learn how to integrate payment systems such as Stripe and Paddle. If you are interested, join the waitlist.